by Jessica To, NIE

Engaging students with feedback is crucial for

productive feedback processes. To fulfil this mission, teachers devote time and

energy to providing written comments on students’ work and arranging

after-school individual consultations. Disappointingly, not all students

approach their teachers after reading the feedback “Please come to see me to

discuss your essay”. Even if some attend the consultation meetings, they may be

passive and seldom take initiative to discuss their problems. Under such

circumstances, students are blamed for lack of motivation for feedback uptake.

This may be partially true. However, this may also signify their lack of trust

in feedback providers. Defined by Tschannen-Moran (2004), trust is “one’s

willingness to be vulnerable to another based on the confidence that the other

is benevolent, honest, open, reliable, and competent” (pp.19-20). Trust

deserves educators’ attention because it is the cornerstone of dialogic

feedback processes. Without trust in feedback providers, students may be

reluctant to accept critiques, discuss learning difficulties and seek

assistance from teachers and peers. This article explains the importance of

trust in feedback engagement and recommends strategies to foster trust in

dialogic feedback.

The role of trust in feedback engagement

Trust plays a pivotal role in effective feedback

communication because it impacts on students’ engagement with feedback. Two

types of trust are pertinent to feedback engagement: communication trust and

competence trust. Communication trust refers to the beliefs in a person’s

willingness to conduct sincere communication, tell the truth and give negative

feedback with good purpose (Carless, 2013). This type of trust is fundamental

for teacher-student feedback exchanges since students would be more

psychologically ready to participate in a dialogue if they believe their

teachers hold them in respect and would not treat their inadequacies with

contempt. Competence trust denotes the beliefs in a person’s ability to produce

quality and useful feedback (Carless, 2013). This type of trust is essential

for peer feedback exchanges as a certain number of students have reservations

about the accuracy of peer comments and therefore are not eager to take part in

peer review activities.

The absence of trust could have repercussions

for students’ feedback engagement. If they lack communication trust in

teachers, they may perceive negative feedback on work performance as offensive

personal remarks (Carless, 2006). This not only affects teacher-student

relationships but also leads to students’ refusal to enact the feedback

received. Furthermore, in a distrust-stricken environment, they may be less

willing to discuss inadequacies in feedback dialogue for fear that exposing

weaknesses to teachers may affect teacher evaluation of performance (Yan &

Brown, 2017). The dearth of competence trust could discourage them from using

peer feedback for academic self-regulation if they doubt the usefulness of peer

comments (Panadero, 2016).

In view of the importance of trust, it is

imperative for educators to enhance communication and competence trust in

feedback exchanges. Table 1 below summarises the definition of communication

trust and competence trust and outlines the strategies for trust building.

Table 1

Strategies for trust building

· Setting a scene for candid

feedback exchanges

Teachers could set the

scene by stating the aim of feedback discussion and setting expectations at the

outset of dialogue as follows:

Example 1 Setting a scene for candid feedback discussion

Students’ anxiety about feedback discussion could be relieved if

they are clear about the purpose of the discussion and could see the value of

an open discussion of problems and weaknesses.

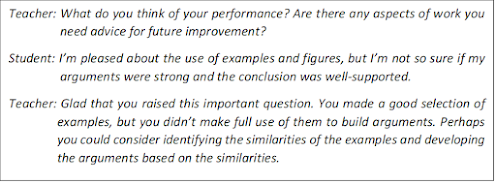

· Co-constructing feedback with

students

Feedback co-construction

involves teachers and students taking mutual responsibility for crafting

feedback messages. As shown in example 2 below, this could be achieved by

students making their feedback requests, followed by their teacher’s response

to their needs.

Example 2 Feedback co-construction

Allowing students to

articulate feedback needs would be helpful for investing their trust in

feedback interaction. When they know their feedback requests are accommodated

seriously by teacher, they would be more motivated to discuss their weaknesses

and would be psychologically ready to accept criticisms (To, 2021). The

prerequisite for feedback co-construction is students’ capability to

self-assess performance and identify their own learning challenges.

· Empathy and attentive

listening

Students’ psychological

safety could be enhanced if teachers demonstrate empathy and attentive

listening in their response to students’ feedback requests or explanation of

learning difficulties. Illustrated by example 3, a teacher could show his / her

understanding of the student’s difficulties and share his / her previous

learning experience in the response.

Example 3 Demonstrating empathy and attentive listening in feedback dialogue

When students feel

teacher’s sincerity, they would be more willing to discuss their learning

difficulties in the conversation. The atmosphere of sincerity could be further

reinforced if teachers demonstrate the sympathetic attitude in regular

classroom interaction (Carless, 2013).

Strategies to develop competence trust

Given students’ prime concern about the quality of peer feedback,

competence trust could be developed through peer feedback training and a

quality check on peer feedback.

· Peer feedback

training

Peer feedback training could be incorporated into pedagogical

activities to increase students’ capability to make academic judgements and

construct peer comments. For example, prior to peer review activities, students

could grade two to three exemplars of varied quality based on their

understanding of assessment criteria and write comments to justify their

evaluative decisions. Then, they could exchange their evaluative judgements and

reasoning with teacher in a plenary session. Through the interaction, they

could notice the judgement gaps and refine their initial understanding of

quality. Teachers could also discuss with students the components of effective

and ineffective peer feedback and demonstrate how to transform the ineffective

feedback into effective ones.

· Quality check on

peer feedback

Teacher monitoring of the effectiveness of peer feedback could be

achieved by different means. Inspired by Han and Xu (2020), teachers could

collect peer feedback forms at the end of peer review and provide feedback on a

random selection of peer comments with the aim of mediating students’

evaluative judgements. Alternatively, teachers could streamline the monitoring

process using online platforms. For instance, when students post drafts for a

collaborative writing project on Wiki or Google Classroom, teachers could have

access to their drafts and peer feedback and offer input to refine the quality

of peer comments during task engagement (Woo et al., 2013).

In conclusion, this article has examined the

role of trust in feedback processes and has outlined some strategies to foster

communication trust in teacher-student feedback exchanges and competence trust

in peer feedback interaction. With a richer understanding of trust in feedback

engagement, educators would be in a better position to design and implement

effective feedback to enhance students’ engagement.

References

Carless, D. (2006). Differing perceptions in

the feedback process. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2),

219-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572132

Carless, D. (2013). Trust and its role in

facilitating dialogic feedback. In D. Boud, & E. Molloy (Eds.), Feedback

in Higher and Professional Education: Understanding it and Doing it Well (pp.

90-103). London: Routledge.

Han, Y., & Xu, Y. (2020). The development

of student feedback literacy: The influences of teacher feedback on peer

feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(5),

680-696. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1689545

Johnson, C. E., Keating, J. L., & Molloy,

E. K. (2020). Psychological safety in feedback: What does it look like and how

can educators work with learners to foster it?. Medical Education, 54(6),

559-570. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14154

Panadero, E. (2016). Is it safe? Social, interpersonal, and human

effects of peer assessment: A review and future directions. In B. Gavin,

& L. Harris (Eds.), Handbook of Human and Social Conditions

in Assessment (pp. 247–266). New York: Routledge.

To, J. (2021). Using learner-centred feedback design to promote

students’ engagement with feedback. Higher Education Research &

Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1882403

Tschannen-Moran, M. (2014). Trust

Matters: Leadership for Successful Schools (2nd edition).

San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Woo, M. M., Chu, S. K. W., & Li, X. (2013).

Peer-feedback and revision process in a wiki mediated collaborative

writing. Educational Technology Research & Development, 61(2),

279-309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-012-9285-y

Yan, Z., & Brown, G. (2017). A cyclical self-assessment

process: Towards a model of how students engage in self-assessment. Assessment

& Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(8), 1247–1262.

https://doi.org/10.1080/ 02602938.2016.1260091